Vladimir Belogolovsky talks to BV Doshi, the first Indian architect to win the Pritzker Prize, for whom architecture is a path that no one else has travelled before to get to a new vista.

India’s most celebrated architect, 2018 Pritzker Prize laureate Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, started his professional education in Bombay in 1947, the year India became an independent nation. But he soon went to London without ever completing it to prepare for the exam at the Royal Institute of British Architects, RIBA. From a friend he found out about Le Corbusier’s projects in India and joined his office in Paris in 1951. He worked there on the designs for the High Court and Governor’s Palace in Chandigarh and then on the Mill Owners’ Association building and Shodhan House in Ahmedabad. Starting from 1955, Doshi supervised the construction of Le Corbusier’s projects in Ahmedabad, where he settled and opened his own practice the following year.

Narrating stories is the essential tool that I use in generating my designs

Doshi met leading architects and engineers such as Kenzo Tange and Buckminster Fuller while accompanying them on their visits to Ahmedabad to view buildings by Le Corbusier. In 1958, he was invited to teach at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, which led to many important acquaintances and subsequent invitations to teach and lecture all over the world. In 1961, when Doshi was assigned to build the new Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, he offered his commission to Louis Kahn and became his associate architect for the project. The next year, at the age of 35, Doshi initiated and founded the School of Architecture, Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT) in Ahmedabad, for which he designed and completed a building in 1968 and where he was teaching until 2008.

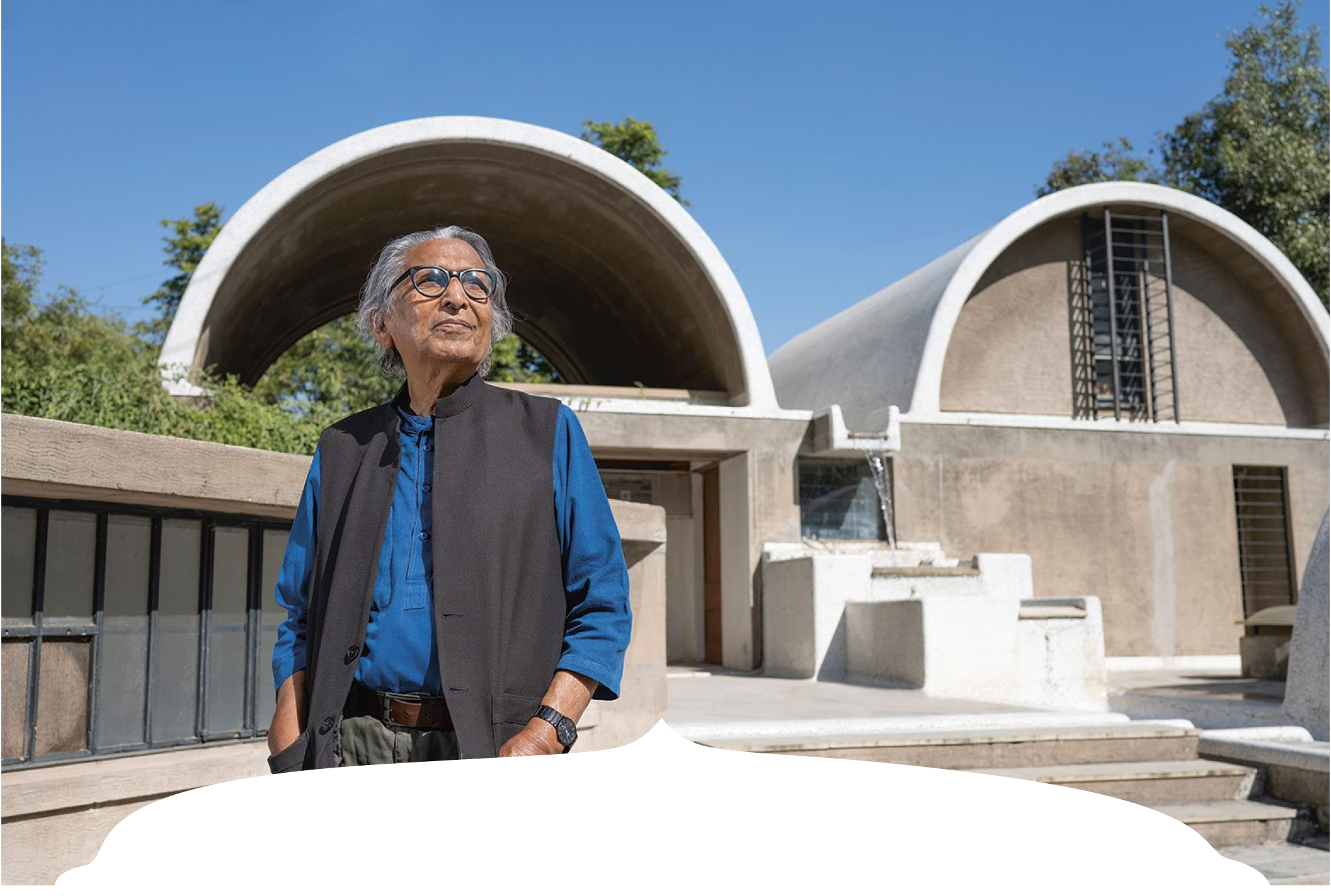

Kamala House, Ahmedabad, India

Image: Courtesy of Vastu Shilpa Foundation

Vladimir Belogolovsky (VB) – You like to say, “Surprise is one of the very important elements for creativity”. Could you touch on how you typically start a new project? How do you try to find a good balance between what is functional and inventive, familiar and surprising, anonymous and personal?

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi (BVD) – It is a very intriguing question, an essential question. I always advocate for the importance of imagery because in my culture and in my own family, stories always play an important aspect of the everyday life. Images trigger thoughts. Thoughts link associations. Associations conjure stories. Stories create myths. Myths generate new narrations and new realities. And whenever there is a client for a project, there is always a question – why do it? There must be a purpose, right? This means there is always a story and there are images, and ideas, and experiences to be shared. From the very beginning there is always a description by the client. If it is a house, then it is about how the client lives and how he or she imagines the new place. This is how it always has been for me – narrating stories, events, and images. Narrating stories is the essential tool that I use in generating my designs.

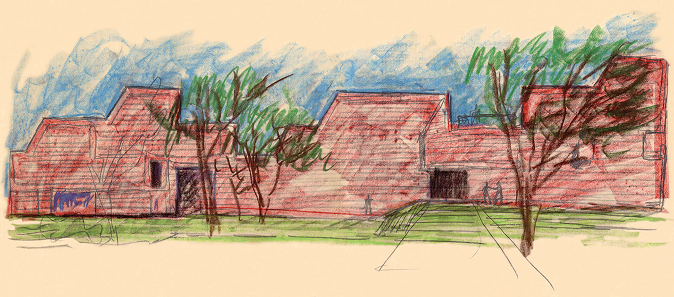

Sketch by BV Doshi of the School of Architecture, Ahmedabad, India

Image: Courtesy of Vastu Shilpa Archives

VB – You were just 35 when you started the School of Architecture in Ahmedabad in 1962. What was your intention there and what kind of pedagogy have you tried to build there?

BVD – I started teaching in America in 1958, first at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. I had also given lectures around the world by then. At that time in India we only had five or six schools of architecture. And we always referred to the Bauhaus, Oxford, Harvard, and so on. Every time there was a foreign reference. And I was asking myself, “What is our reference? What is my reference about India?” Around the same time, I had an assignment to teach in Philadelphia. And when I went to the old building at the University of Pennsylvania, the interesting thing was that when I went to their studio there was a series of studios – one long room with one studio after another. So, you could walk freely there from one to the next. So, I realised that education implies exposure, assimilation, dialogue, and exploration. Those things really affected me a lot.

When I came back to India, I was thinking about a new school and the whole question was – what kind of school would it be? My impression was – it should be a school without doors. It should have no boundaries. And the site that I selected was where the brick kiln used to be. When I went to the site I was thinking – shouldn’t a school be a journey? It should be an exploration, a part of nature. It should be about experiencing a movement of shadows that one goes through. And I was thinking about the north light, which is the best light in India. I was thinking about ventilation, natural cooling, and what constitutes a comfortable place. How can I create a building, in which I would be conscious of nature, of breathing, of space, and of changing light?

School of Architecture, now called CEPT University, Ahmedabad, India

Image: Courtesy of Vastu Shilpa Foundation

VB – There is a continuous theme that runs through your work and that is the idea of the development of an appropriate language for modern Indian architecture. Could you touch on this issue of identity and the importance of making architecture belonging to its culture and place?

BVD – I think Le Corbusier’s arrival in India and the school that he started in Chandigarh was very important. And we were thinking about our own ways of practicing architecture in Ahmedabad. I think the point was to create something, which is native, rooted to the place. Only then we could talk about our own beginning. When the Bauhaus was started it was all fresh. That was the spirit. Our attitude about answering these questions – what is suitable, what is appropriate, meaningful, and what should be taught? We did not want to imitate someone else’s approach and adaptations of other sources. We wanted to find our own identity and our own education system.

My impression was – it should be a school without doors. It should have no boundaries.

VB – You worked very closely both with Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn. You once said, Kahn’s buildings are for meditation, whereas Le Corbusier’s buildings “sing”. Could you elaborate on that beautiful phrase?

BVD – I think when there is a rhythm, when there is a pause, when there is a sense of proportion, and when these things are all put together, they make up a synthesis and they sing together. They rhyme together. Then you let all these beautiful qualities unfold one after another. It is like a beautiful dance. Le Corbusier’s buildings are made of forms, light, and space, and fluidity. Each of his buildings is a beautiful object. Kahn’s buildings, on the other hand, were typically built as groups and campuses. Le Corbusier’s buildings were isolated, but full of richness, volume, light, and space.

When I went to work for Le Corbusier in Paris, I was still very young, and I learned many things from him fresh. There was no one style or one theory at his office. Look at the vast difference between his Chandigarh’s Capitol complex buildings and Ronchamp chapel, or his houses. Each project is very inventive and entirely independent. When you see that as an example, then naturally, you don’t think that his way is the only way. He had so many ways. That’s the main lesson I took from him – there are many ways. I think it was my luck that I did not complete a formal school of architecture. [Laughs.]

Amdavad ni Gufa (The Cave of Ahmedabad)

Image: Iwan Baan, Courtesy of Vastu Shilpa Foundation

VB – In the 1989 letter to your three daughters you said, “Break away from all the rules - forget history books. Go back to your inner perceptions. See things as if you are noticing them for the first time. Only then you will be able to do something of your own”. Why do you think it is important to keep reinventing architecture continuously again and again?

BVD – I think we always fall in a trap of familiarity, conventions, general opinions, and public considerations. And I think those are the issues that we always get influenced by and we want to do something similar. The same is with architecture. What is architecture? Is the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore not architecture because it is not simply a building? It is a procession; in which you are experiencing things. The word architecture itself is a trap. So, when we think of architecture, we think of what is common, what is familiar. If something is appreciated by others why not follow the path, right? But to me architecture is a path that no one else has traveled before to get to a new vista.

Architecture is a path that no one else has traveled before to get to a new vista.

VB – You said, “If architecture is a living thing why not create many purposes for it?” Could you elaborate?

BVD – Very simple – do I want to be like a robot or a human being? Do I follow all the instructions given to me? Look at children – how they go everywhere to discover something and then enjoy it. But gradually we accept such ideologies and conventions that if everyone doing something or likes something than it must be good for us as well. I think the moment you are a child you are free. The moment you are a grown up you get a lot of baggage.